Introduction

As modern power systems expand toward Extra High Voltage (EHV) and Ultra High Voltage (UHV) levels, insulation coordination has become a cornerstone of reliability and safety.

Every kilovolt increase magnifies the electrical, mechanical, and environmental stresses on insulators and substation equipment. Even a minor insulation failure can cause cascading blackouts, serious equipment damage, or safety hazards.

To prevent this, engineers rely on insulation coordination—the science of ensuring every component in a power system can safely withstand voltage stresses caused by lightning strikes, switching operations, or system faults.

The goal is to design insulation that is strong enough to resist overvoltages, yet not overdesigned to the point of being uneconomical.

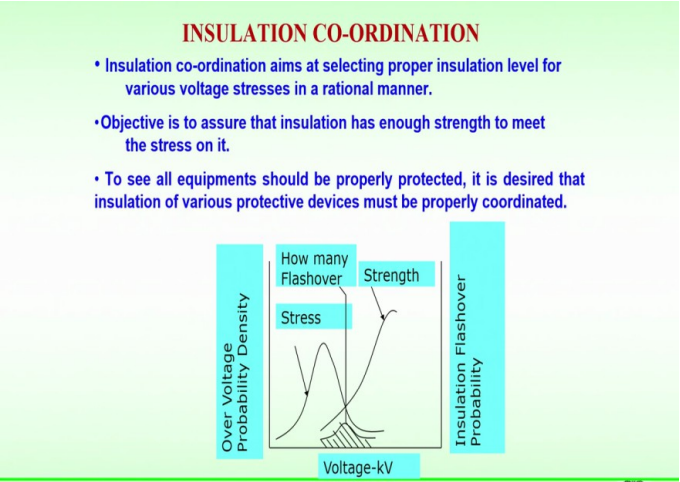

What Is Insulation Coordination?

Insulation coordination means selecting appropriate insulation levels for equipment and transmission lines so that:

- Insulation failure occurs only in rare, extreme conditions.

- Protective devices like lightning arresters act first to divert surges.

- The system remains both safe and cost-efficient.

Objective

Ensure that insulation strength always exceeds voltage stress under all expected conditions, while maintaining acceptable risk and cost balance.

Probabilistic Design Concept

Both voltage stress and insulation strength vary statistically. They are influenced by temperature, humidity, aging, pollution, and manufacturing differences.

Instead of using a fixed “safe” number, engineers design insulation probabilistically. They accept a tiny probability of failure—because the simultaneous occurrence of high stress and weak insulation is extremely rare.

This design philosophy reduces overall line cost and makes insulation systems more efficient without compromising reliability.

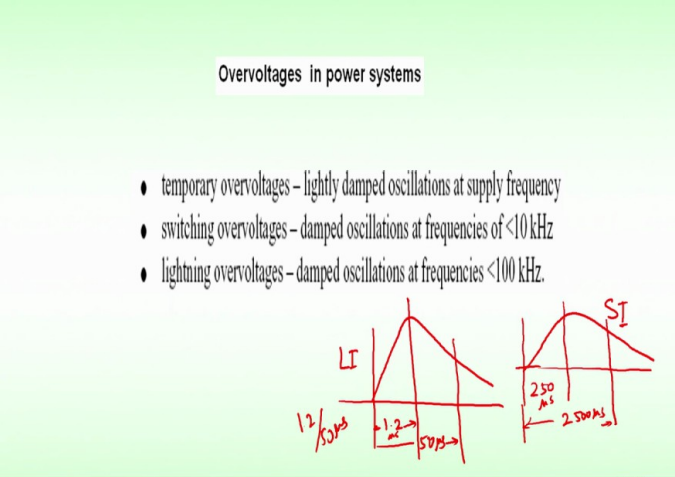

Classification of Overvoltages in Power Systems

Overvoltages are transient or temporary rises in system voltage above the normal rated value. They are broadly classified into external and internal categories.

1. External Overvoltages

Caused by natural or man-made disturbances such as:

- Lightning strikes: Direct or induced surges on towers or conductors.

- Back-flashovers: Current flowing from tower to line due to lightning.

- Electromagnetic pulses (EMP): Nuclear or solar-induced disturbances.

2. Internal Overvoltages

Generated by system operations or faults:

- Switching surges: Circuit breaker operation, capacitor switching, or fault clearing.

- Load rejection or Ferranti effect: Causes voltage rise at light load.

- Arcing ground and resonance: Sustained overvoltages from ground faults.

Each category demands specific protective measures—such as surge arresters, proper grounding, and controlled switching.

Common Types of Overvoltages and Waveforms

| Type of Overvoltage | Frequency | Typical Waveform (μs) | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightning Impulse | <100 kHz | 1.2 / 50 | Atmospheric discharge | Steep and high magnitude surge |

| Switching Impulse | <10 kHz | 250 / 2500 | Breaker operation | Long-duration transient |

| Temporary Overvoltage (TOV) | 50 Hz | Oscillatory | Load rejection, Ferranti | Sustained low-frequency overvoltage |

Lightning impulses produce the sharpest voltage fronts, while switching impulses are slower but can reach high magnitudes in EHV systems.

Both must be carefully considered when determining the insulation level.

Insulation Coordination Curve

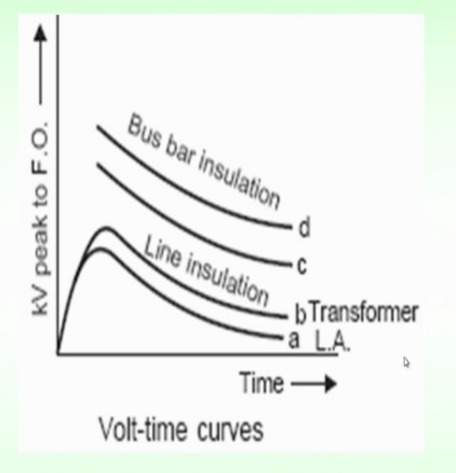

In a properly coordinated system:

- The voltage stress curve (actual overvoltages) lies below

- The insulation strength curve (equipment withstand level).

Lightning arresters have the lowest protective level, meaning they operate first—diverting excess energy and protecting transformers or breakers.

This hierarchy ensures reliable operation even during severe transients.

Voltage Level vs. Dominant Design Factors

| Voltage Range | Dominant Factors Affecting Insulation Design |

|---|---|

| Below 4 kV | Mechanical clearance only |

| 4–33 kV | Corona discharge and lightning surges |

| 66–220 kV | Switching surges and lightning surges |

| 400–800 kV | Pollution, contamination, and switching surges |

| Above 800 kV | Pollution and contamination dominate |

At higher voltages, environmental contamination becomes the main concern for insulation performance.

Pollution and Contamination Effects

Dust, salt, and industrial pollution accumulate on insulator surfaces. During rain or fog, these deposits dissolve and create a partially conductive film, which may lead to surface leakage currents and eventually flashovers.

Prevention Methods:

- Increase leakage distance (mm/kV).

- Use silicone rubber or composite polymer insulators with hydrophobic surfaces.

- Apply RTV coatings on porcelain insulators.

- Regularly clean and monitor insulators in polluted regions.

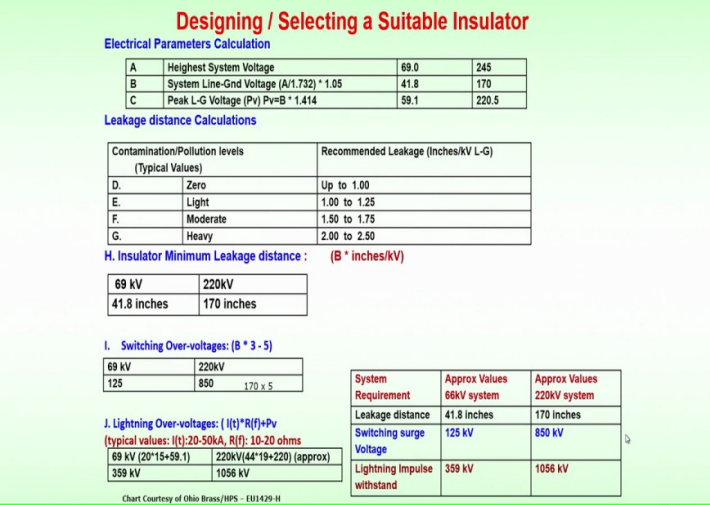

Electrical Design Parameters

1. Strike Distance (Dry Arcing Distance)

The strike distance is the shortest air gap between metal fittings of an insulator under dry conditions.

It determines the voltage at which flashover occurs through air.

Example:

The distance between the cap and pin in a string of suspension insulators dictates flashover voltage during lightning surges.

Formula (approximation):

V = k × d

Where:

V = Flashover voltage

d = Strike distance

k = Constant depending on configuration and environment

2. Leakage Distance

The leakage distance is the total surface path between the metal fittings of an insulator.

It governs insulator performance under wet and polluted conditions.

Typical recommendations:

- 17–25 mm/kV for clean environments

- 25–31 mm/kV for moderate pollution

- 35 mm/kV for heavily polluted zones

Example calculation:

For a 220 kV system in moderate pollution:

(220 / √3) × 25 = 3175 mm (approx.)

Thus, an insulator must have around 3175 mm of surface path to prevent flashover under such conditions.

3. Mechanical Strength Criteria

Insulators are not only electrical barriers but also mechanical supports for conductors.

They must withstand:

- Conductor tension

- Wind pressure

- Ice or snow load

- Vibration

- Short-circuit mechanical shocks

Typical mechanical strength (tensile / compressive):

| Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Porcelain | 30–100 | 240–820 |

| Glass | 100–120 | 210–300 |

| Polymer | 20–35 | 80–170 |

| Resin-Bonded Glass Fiber (RBGF) | 1300–1600 | 700–750 |

Porcelain insulators must not exceed 50% of rated strength; cracks often lead to electrical punctures.

Typical Insulation Design Example: 220 kV Transmission System

Let’s calculate the main insulation parameters step by step.

Step 1: Determine System and Peak Voltages

Nominal system voltage = 220 kV

Maximum system voltage = 245 kV

Line-to-ground voltage = 220 / √3 = 127 kV

Peak voltage = 127 × √2 = 180 kV

Step 2: Leakage Distance

Depending on pollution level:

For moderate pollution = 1.5 – 1.7 inches/kV

Minimum leakage distance = 127 × 1.7 ≈ 215 inches (≈ 5450 mm)

Step 3: Switching Surge Level

For 220 kV systems, the switching surge factor ≈ 5 × line-to-ground voltage

170 × 5 = 850 kV

Hence, the switching surge level is approximately 850 kV.

Step 4: Lightning Impulse Voltage

Considering lightning current = 44 kA and surge impedance = 90 Ω:

V = I × R + Vsystem

V = (44,000 × 90) + 220,000

V = 4,180,000 + 220,000 = 4.4 MV

Only about 20–25% of this appears across insulation after surge dissipation, so the insulation withstand level ≈ 1.05 MV.

Summary of Design Values for 220 kV System

| Parameter | Typical Value |

|---|---|

| System voltage | 220 kV |

| Max voltage | 245 kV |

| Line-to-ground voltage | 127 kV |

| Peak voltage | 180 kV |

| Leakage distance | ≥ 215 in (≈ 5450 mm) |

| Switching surge voltage | 850 kV |

| Lightning impulse withstand | 1050 kV |

Material Innovations and Modern Trends

Modern transmission systems use composite polymer insulators in place of porcelain and glass.

Advantages include:

- Lightweight and easy handling

- High hydrophobicity

- Superior performance in polluted regions

- Resistance to vandalism

Challenges:

Polymer insulators can degrade under UV exposure and require surface condition monitoring to maintain performance.

Testing and Standards

To ensure insulation reliability, every high-voltage component undergoes laboratory testing before installation.

Common tests include:

- Lightning impulse test (1.2 / 50 μs)

- Switching impulse test (250 / 2500 μs)

- Power frequency withstand test

- Wet and pollution flashover test

Key standards:

- IEC 60071 – Insulation Coordination

- IEC 60383 – Insulators for Overhead Lines

- IEEE C62.82 – Surge Arresters

💰 Economic Considerations

Overdesigning insulation increases line weight, tower size, and total cost. Underdesigning raises the risk of failure.

The best approach is economic optimization—balancing cost with reliability.

A well-coordinated design can reduce line costs by 15–25% while maintaining safety margins.

Designers must evaluate the cost of possible failure versus the cost of additional insulation to find the optimal level.

🌍 Future of Insulation Coordination

The emergence of smart grids and HVDC systems introduces new challenges.

Fast transients from converters, renewable integration, and mixed AC/DC environments require advanced modeling tools.

Modern methods include:

- EMTP and PSCAD simulations for transient analysis

- Digital twins for dynamic insulation performance prediction

- AI-based monitoring of insulator leakage and flashover risk

Conclusion

Insulation coordination is not merely a design step—it is the backbone of power system reliability.

By understanding overvoltages, designing proper insulation levels, and coordinating protective devices, engineers ensure that the grid remains stable during lightning strikes, switching operations, and unexpected faults.

In essence, insulation coordination keeps the lights on when nature or the network tests the limits of the system.